Custom Software: Organizations develop their own custom software from scratch, rather than use or customize packaged software for three reasons. First, no packaged software meets the required specifications, and modifying existing software is too difficult. Second, the company plans to resell the custom software at a profit. Third, custom software may provide the company with a competitive advantage by providing services for customers, increasing management’s knowledge and ability to make good decisions, reducing costs, improving quality, and providing other benefits. Only custom software can provide such a competitive advantage because the competition can easily buy packaged and customized software. Merrill Lynch recognized such a competitive advantage when it planned to invest $1 billion in software (and associated hardware) to allow its financial consultants to operate with mobile computers at customer sites[1].

Custom software is expensive to produce, costly to maintain, subject to bugs, and usually takes many years to develop. Not only does this development time delay the benefit, but it reduces the value of the software as company needs and the competitive environment change constantly. Finally, if software developers can mimic the key features of the software’s design and resell it to a company’s competitors, they may quickly dilute any competitive advantage the company has gained.

Mutual originally developed CNS because the available packaged software did not meet its needs and because it felt that it could achieve a competitive advantage with CNS. At the time it developed CNS, no software provided an integrated view of a customer across multiple insurance products. CNS gave Mutual agents a competitive advantage by allowing them to cross-sell products where appropriate. Conder has learned that about one-half of all companies in the insurance industry who replace their software use custom software, primarily for these same reasons. By contrast, in the health care industry, less than one-fifth use custom software[2].

Managers who decide to develop custom software must decide whether to use internal company resources or to hire a company that specializes in software development. VARs develop customized software cost-effectively because they have substantial expertise in the base software product, but this advantage disappears for custom software because they cannot use preexisting packages. Small organizations that lack internal resources for software development may create custom software by paying another company to do it. Boston Software Corporation and ECTA Corporation, for example, develop software for companies in the insurance industry[3]. Managers in large organizations usually must use internal IS personnel or let the IS staff decide who will develop the software. Sometimes company policy allows functional managers to seek development bids from both internal and external candidates. Grange Mutual Casualty Company, an Ohio-based insurer with annual premium sales of $500 million, has outsourced some of its development and operations to Policy Management Systems Corporation[4].

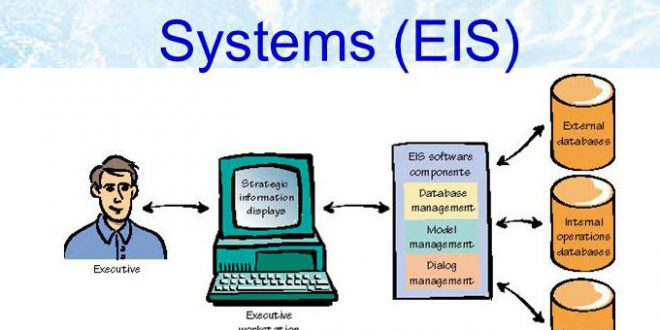

THE POTENTIAL OF VARIOUS EIS FEATURES

Integrated solutions coordinate the activities of suppliers, distributors, and customers. This integration, called supply-chain management, requires the cooperation of companies outside of the company’s own and a secure way of communicating between them. Supply chain management can reduce the costs of a company with $600 million in annual sales by as much as $42 million. Companies using supply chain management needed only two weeks on average to increase production by 20 percent compared to several months without supply-chain management. Also, companies with supply-chain management delivered goods on time 96 percent of the time compared to 83 percent for the average company[5]. Ames, the $200 million maker of garden tools, and Ace Hardware Corporation use Manugistics supply-chain management software to keep track of and replenish Ames’s products sold in Ace hardware stores[6].

The grocery industry calls supply-chain management efficient consumer response (ECR). ECR software breaks barriers between trading partners, such as retailers and manufacturers, and between internal functions such as category management and product replenishment (see Figure 4.6). Companies such as Land O’ Lakes Inc. and Kellogg Company have begun to implement integrated ECR packages to improve internal processes, gain greater efficiency in distribution, and globalize their operations[7]. Oracle and SAP have moved into the ECR market to respond to the growing demand with software derived from their manufacturing packages.

Enterprise-resource-planning (ERP) software products, such as those developed specifically for each industry by SAP, Oracle, Baan, and PeopleSoft, provide seamless support for the supply-chain, value-chain, and administrative processes of a company. They integrate diverse activities internal and external to the company, support many languages and many currencies, and help companies integrate their operations at multiple sites and business units.

Most ERP applications are customized products. The major vendors begin with an application template that is pre-customized by industry. Then, the vendors, consultants, or the company purchasing the software further customize it to meet individual company needs. Although the ERP vendors build their software to minimize the amount of customization and to simplify the customization process, most large companies spend anywhere from 100 percent to 500 percent of the cost of the software for its customization. An integrated ERP solution lets managers analyze their operating units as a whole and make decisions from a global perspective. Integrated ERP software eliminates the need to build bridges between applications to share data. For example, sales managers can respond to a manufacturing or ordering plan that might affect the availability of a product. The Monsanto Company, Dow Chemical, and the DuPont Company, all major chemical manufacturers with global operations, have converted their business systems to ERP software products known as R/2 (mainframe based) and R/3 (client/server based), packages produced by SAP AG. The conversion allows them to support simplified business processes as well as communication and collaboration worldwide[8].

GATX Capital Corporation, a lessor of commercial aircraft,customized the R/3 version of SAP to fit its business. Now it plans to sell its customized work to its competition.16 ERP software often requires companies to change their processes to accommodate the software. ERP lets them introduce improved, redesigned processes because ERP software incorporates the best processes of companies in the industry.

However, when a company has unique processes that give it a competitive advantage, adoption of ERP software can have negative consequences. ERP and any integrated software may not provide as many features or provide them as well as software specifically designed for a particular application, such as inventory management. Functional managers and general managers need to choose between the best software they can find in each functional area or an integrated package that provides 80 to 90 percent of the features they need in each area. In making this decision, they need to consider the cost of customizing the software to achieve the additional 10 to 20 percent of functionality.

ERP software has not penetrated the service industries because managers are less likely to use systems that their competitors can purchase. Nevertheless, the economic advantages of customized and packaged systems and the success of ERP in manufacturing industries have accelerated the acceptance of integrated packages for a subset of functions in many service industries. Springer-Miller Systemshas penetrated the hotel market with software that handles all front- and back-office functions. The software performs and integrates such tasks as maintaining guest histories, booking golf tee times and dinner reservations, preparing correspondence, maintaining reservations, and managing multiple

properties in a chain.

CONCLUSION

Modifying vertical application software to deal properly with dates in the year 2020 and beyond is a major problem worldwide. The Gartner Group, a well-respected industry forecaster, estimates the cost to be between $300 and $600 billion. Other estimates run as high as $1.6 trillion. According to Viasoft, a consultant involved in these conversions, a typical Fortune 1000 company will spend between $10 and $15 million, consume more than 14 decades of staff time, and require a peak staffing of 48 programmers. Surveys have indicated that 83 percent of companies plan to spend more than 25 percent of their information systems budgets in 1998 and 1999 just to fix their applications for the year 2020

Companies can take three approaches to fixing the problem:

- Use Automated Tools. These tools examine each line of code, identify those that likely refer to dates, and, with some user help, alter them to deal properly with a four-digit year. Vendors and consultants for Tampa Electric, the Florida utility, estimated that it would cost the company about $1 per line to fix its 4.5 million lines code in their 6,000 mainframe programs. After completing a pilot program with automated tools, Tampa Electric estimates that it can complete the task at a substantially lower (although yet unspecified) cost using no more than seven employees over a 22-month period.

- Replace Existing Software with Year 2020 Compliant ERP Products. Because ERP software affects every process in the company, an ERP installation in a large company may take two or three years.

REFERENCES

- Kaniclides, A., C. Kimble.(1995) A Development Framework for Executive Information Systems. Proceedings of GRONICS’95, Groningen, The Netherlands, February.

- Kimble, C., (1997) Assessing the Relative Importance of Factors Affecting Information Systems Success, University of York Technical Report Series, YCS 283, Department of Computer Science, York, UK.

- Salmeron, Jose L. and Herrero, Ines. (2005) An AHP-based methodology to rank critical success factors of executive information systems. Computer Standards & Interfaces, Volume 28, Issue 1, July.

- Salmeron, Jose L.(2002) EIS data: Findings from an evolutionary study. Journal of Systems and Software Volume 64, Issue 2.

- Thierauf, Robert J. (1991) Executive Information System: A Guide for Senior Management and MIS Professionals. Quorum Books, New York.

[1] Thierauf, Robert J. (1991) Executive Information System: A Guide for Senior Management and MIS Professionals. Quorum Books, New York.

[2] Salmeron, Jose L. and Herrero, Ines. (2005) An AHP-based methodology to rank critical success factors of executive information systems. Computer Standards & Interfaces, Volume 28, Issue 1, July, pp.1-12.

[3] Salmeron, Jose L.(2002) EIS data: Findings from an evolutionary study. Journal of Systems and Software Volume 64, Issue 2, pp.111-114

[4] Kimble, C., (1997) Assessing the Relative Importance of Factors Affecting Information Systems Success, University of York Technical Report Series, YCS 283, Department of Computer Science, York, UK.

[5] Kaniclides, A., C. Kimble.(1995) A Development Framework for Executive Information Systems. Proceedings of GRONICS’95, Groningen, The Netherlands, February, pp. 47 – 52.

[6] Salmeron, Jose L.(2002) EIS data: Findings from an evolutionary study. Journal of Systems and Software Volume 64, Issue 2, pp.111-114

[7] Kimble, C., (1997) Assessing the Relative Importance of Factors Affecting Information Systems Success, University of York Technical Report Series, YCS 283, Department of Computer Science, York, UK.

[8] Salmeron, Jose L. and Herrero, Ines. (2005) An AHP-based methodology to rank critical success factors of executive information systems. Computer Standards & Interfaces, Volume 28, Issue 1, July, pp.1-12.